Healthcare Voice Assistants Return Control Over Care to Clinicians and Patients

One of the main differences between human language and animal communication is the level of cooperativeness it allows us to achieve. Language allows us to figure out what others think, plan, and want, and collaborate with them, walking towards a common goal, whatever bold, unrealistic, or imaginative it is. Human language is, by nature, a top tool for us to collaborate.

Now, if we’re to view our language and our voice as a technology, it would be fair to call it a thing most people are able to handle proficiently, even effortlessly. We’re used to speaking while busy with something else. We’re — usually — reflexively re-focused when others start speaking to us. Voicing our thoughts is also the most straightforward and efficient way to get others to understand us.

So, if we were to apply our more or less native tool to control technology, it would take a little time to get used to it, right?

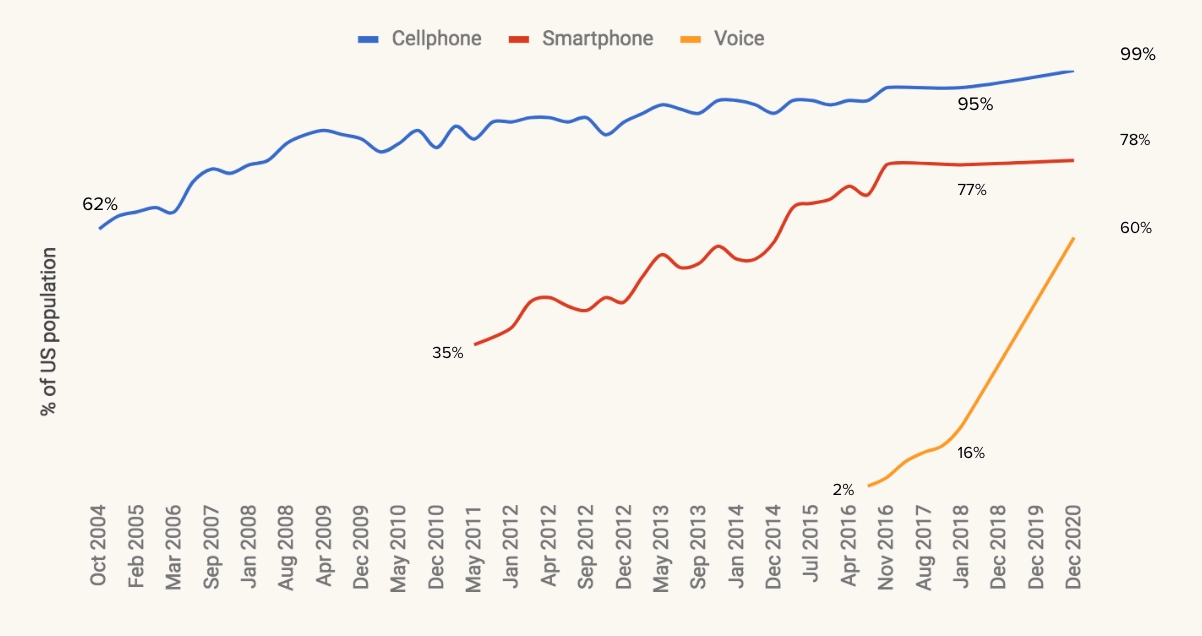

Amazon Alexa was released less than six years ago. Siri — a bit earlier. Now, a technology that operates as voice assistants is adopted faster than any consumer-facing tech. No wonder, considering it has, like, the lowest threshold for users: they just have to speak.

It comes as no surprise that the healthcare industry actively utilizes this technology.

Healthcare is a field where communicating with patients is what doctors want to do the most, but cannot, due to cognitive burden. Where hospital departments are disconnected in terms of which patient data they handle and how they can be effectively, quickly transferred to the point of care. Where patients forget to take their medication, struggle with loneliness and anxiety, are frightened to make an appointment due to costs of services — or too nervous to not call the ambulance after googling their symptoms. You understand.

So let’s talk about what technology voice assistants use and what they’ve already improved in our siloed and troubled domain.

How do we get machines to talk and understand us?

The correct question actually should be: “How we could teach machines to understand what we’re saying and respond adequately and like a human would.” It’s a very challenging task: consider all accent, slang, phrasal verbs and tons on a variation on the theme of formal language we’re using daily. For healthcare, it is way harder, due to medical terms (which are not unified between doctors of different departments), professional slang (which also varies from one professional to another), and giant domain knowledge [for machines it will be conclusive, clinical data] that is required to figure out what’s going on.

In fact, the correct term for a machine to “understand” what we’re saying, would be “recognize,” because algorithms will search the combination of words you’ve used among the database of knowledge it’s possessed and provide you with a most probable match. That will be speech recognition technology, that uses, in particular, Natural Language Processing (NLP) algorithms to find the said matches. Then, the process of speech synthesis activates, and, using the right responses in text from the domain knowledge base and circumstantial facts about users’ personality, surroundings, and the situation, selects right speech response. All the algorithms needed for a machine to recognize you and talk to you are up to highly complex deep neural networks, that are fascinating, but irrelevant for our healthcare-centric article.

Why healthcare is hesitant to adopt voice assistants?

We both know healthcare is hesitant to adopt tech things; that’s a rule. For a voice assistant tech to get onto doctors’ shoulder, the product team has to ensure there will be a) no problem with regulations, b) smooth adoption, c) [a bit] of understandable, well-structured onboarding. Especially if the technology is, for example, visioned to be in the exam room, help surgeons, etc.

For that to happen, you need to do work tech people don’t like to do, as far as surveys of healthcare executives show. Collaborate closely with doctors and other medical professionals from the start. Invest in security as you mean it. Get intimately familiar with HIPAA/FDA/CE/whatever other regulations exercise control over the healthcare industry and patients’ data in there. We actually wrote an article (mildly scolding one) that answers on why stakeholders don’t want my healthcare product questions, so. That partially might be the case.

The other part of reasons for hesitancy will be specifically voice-assistants-related issues. We want our virtual assistants to behave humanly. We want to learn how to use it quickly. Doctors, specifically, want minimum unnecessary interactions with it while patients’ visit, insights from patterns they didn’t notice [per request], and respect.

That is related to uncooperative, slow, and too intrusive EHRs’ interfaces. Which also explains healthcare professionals’ doubts about any new tech. After HITECH, tech promised to help doctors, but now it occurs that the cognitive burden they put on clinicians led them to burnout which becomes “the biggest public health crisis that we don’t talk about,” as Punit Soni, CEO of Suki, said. It’s only natural they don’t trust new technologies. When you’re using an iPhone, but work on Windows XP on the work, you’ll be just about as trusting as you’d expect.

So, yeah. To get into hospitals with your voice assistant tech, you need to make it really invisible and very helpful. Let’s take a look at examples of such assistants in the industry. Starting with consumer-facing apps.

Voice assistants for patient's care management

So, imagine that every time you planned to go to the doctor, you actually go there. We’re willing to bet it would allow you to avoid at least a few uncomfortable, unfortunate situations. That’s kind of thing voice assistants in patients’ homes aim to mitigate.

They keep track of whether or not users are taking their meds, if they’re prepared for a refill, if there are some side-effects their doctor should be aware of. Per request, they may find the optimal price for the next pill bottle, and even issue a recipe from users’ clinicians. In one word, there is some management going on, and its positive effect on care outcomes is obvious. For one thing, regularity is a success for patients. For another, there’ a certain amount of additional control voice assistants provide, which is very important for people with attention or memory issues, senior people, etc. It’s also just nice to have support from a machine that can’t make mistakes.

For medication adherence issues — which leads to up to half of all treatment failures in the USA — voice assistants can solve more complex behavioural challenges. They can prevent patients from stopping refills by connecting them to doctors/offering them cheaper analogues/simply reminding about a refill. Usually, when it occurs patients stopped refilling, it’s too late to intervene and the course needs to be started over. So, as we said, reliability advantages.

Patients who refill their meds often just put a bottle on a shelf and forget about it (especially if it’s insurance-provided meds that they’ve already stopped taking). That is far from efficient: for patients, for doctors’ understanding of patients’ health, and for insurers. Voice assistants — again, via reminders, — can easily fix that.

They can offer health advice by helping people track their mood and their treatment progress, offering different other health options after pills reminders. Voice assistants can help shift the reactive way of dealing with our health [“I’m sick, so I have to take a pill.”] to proactive [“I want to be healthy, what should I do?”]. So, for instance, after you complete your course, you still do 15-minutes exercises, following instructions from a speaker — or use it to get a few healthy meal suggestions.

Apart from classic tracking-for-wellness things, there are other wonderful smart speakers that work as a baby monitor and listen to babies’ breathing through the white noise. That allows parents to make sure their babies sleep well. It was developed by the University of Washington’s researchers.

Voice assistants can provide some patient education as well, right? Education and awareness spreading is a big deal for healthcare. For one, there are lots of misinformation and outright lies that cause panic, anxiety, and drive patients to decisions that are not good. Like the Covid-9 situation. Like vaccines and autism. Consumer-facing voice assistants, if clinically approved and designed to speak in a language that is understood by mere mortals, provide patients’ with truthful, calming information on whatever they’re concerned about. Educational features are also extremely useful for settings in post-acute care, after surgeries or intense illnesses. If one can drink alcohol, when on antibiotics? If one can bathe, if after tonsillectomy? And so on.

That leads us to the point of symptom-checking algorithms. Even doctors google their symptoms, so they understand the urge to check the symptoms up very well. It’s actually a legitimate thing to do, because by searching what the pain in our wrist means, we’re trying to reach a fraction of understanding and control. Both are very good for our stress levels.

However, Google search/Reddit medical thread/Quora shouldn’t be perceived as medical advice or a solid ground for self-medication. That’s first. Second is the fact that instead of stress relief, we often get more stress.

Voice assistants here don’t give Definitive Medical Opinion as well, but, being tested and created with patients wanting to get a) clinically relevant answers, b) relief in mind, they are most likely answer to a basic coughing fit with a basic “it’s a cold” response, without lung cancer, pneumonia, and other diagnoses that paralyze us with fear.

Conversational interface, being supportive little helper, will then offer users to schedule an appointment with clinicians (offline or online — yes, telemedicine services also can be connected to an interface, but we’ll talk about it later), recommend few simple things to do to feel better, and may even propose them to ask for a sick leave at work.

Voice assistants are pretty special among technologies that are used to manage care because being ultimate attention captivators, they have a potential to create an environment of the continuous care process, where patients are engaged and more closely connected to providers.

Finally, voice assistants can help patients pay their insurance bills or change insurance options, and buy a new one. If Alexa can’t find an option that fits their financial or care-related requirements, she will direct them to Liberty Mutual Insurance.

The easy learning curve is what differentiates different smart speakers from smartphones: people can get a hold of it very easily, whether they’re 7 or 87 years old. There are no device boundaries, no new, complex skills to gain.

Voice-enabled AI as assistive technology

One of the primary segments of voice-enabled virtual assistants market’s audience is people with visual impairment and limited mobility (despite the fact that some of these technologies weren’t designed with accessibility in mind.)

For instance, Alexandra Vtyurina from the University of Waterloo with a team designed VERSE (Voice Exploration, Retrieval and Search.” Their invention combined the high "engageability" of voice assistant technology with a screen reader mechanism that is very familiar for people with visual impairments. In such a way, this team managed to compensate for the common limitation of voice assistants — they usually can’t dive deeply in text content — and allowed their users to control devices via voice and still enjoy the books, easily navigating through their content.

Microsoft’s Seeing AI application widens and simplifies interactions with the world for people with vision difficulties. Initially, the app allowed people to take a photo of a text, document, barcode, currency, or even handwritten message or note — and voiced what was written there. Now, Seeing AI can describe colours of an object or scene around users, adjust audio to a brightness around them, and recognizes users’ friends and even emotions.

And, this February, TNW published a story about a Japanese travel project by Chieko Asakawa for people with visual impairments. It’s a navigation robot shaped like a suitcase that recognizes users’ surroundings, location, and even people via its cameras — and guides them to the needed destination through haptic (vibration of a handle) and vocal (AI’s voice in earbuds) tech.

As for voice assistants for people with limited mobility, we remember last year’s case with Google giving away 100,000 of Home Minis to those who live with paralysis. The blogpost, announcing about initiatives, was written by Garrison Redd — who lives with paralysis — via Mini. Among other things, he tells how easy it was to connect his thermostat to the device to be able to control the temperature, how he uses it to follow his schedule, call people, listen to audiobooks, etc. Read it, it’s really cool.

Quiet recently, Intuition Robotics, an AI company that’s famous for its intelligent countertop-helper — raised $36M in Series B. Here’s how it looks like:

It’s called ElliQ, and ElliQ devices spent more than 10 thousand days in the homes of senior Americans in the last year. Each spends at least 90 days with ElliQ. The company aims to employ a proactive approach to interaction with users and consider it a more comfortable thing for senior people.

And another cool voice technology we want to use as an example is Livio AI’s connected hearing aid. Apart from the fact it’s, well, works as a hearing aid, recognizes speech and is integrated with a virtual assistant, it connects to smartphones and: can translate speech in other languages right into people’s ear; detect users’ movement and activity, allowing people to track their physical health and improve it; stream audio content. The most recent feature is Livio detecting people’s falls and notifying their emergency contacts.

There are, of course, a lot of limitations for voice assistants application in the accessible devices field. For once, there are difficulties from recognizing what people with speech impairment are saying, which are being fixed via inviting different people to donate samples of their audio. But it’s predicted that the voice-enabled accessibility device market will continue to grow, which is a rather good forecast. Technologies are already bringing so much more improvement and independence for people who have difficulties in some interactions with the world, and there’s a reason to believe they will continue to do so.

Speech as a biomarker

And back to the proactive iterations. Since recently, Alexa can recognize if users have a cold and recommend them to connect with doctors and then order medications.

In this case, Alexa uses changes in usual users’ voice — hoarse intonations, lower tone and volume, additional throaty noises all of us hate — as a sign of sickness. She uses a manner of speech as a biomarker, as evidence something has changed and needs to be addressed.

In the same way as Alexa, speech-capturing and analyzing technology can detect first signs of cognitive decline, detect PTSD, depression, and even coronary artery disease. That makes voice assistants a pre-diagnostic tool: they capture meta-data from the way people speak, and, through, for instance, patient portal or EHR, doctors see — per users’ requests, of course, — real-time reports of how their patients feel. That opens a lot of opportunities for preventive, timely interventions, personalized care plans, and more deep and meaningful relationships between doctors and patients.

Voice assistants in hospitals

Doctors’ and nurses’ communities in social media talk a lot about burnout in clinical settings. Burnout levels are very high due to various reasons, including cumbersome schedules, outdated technology in hospitals, and grandiose administrative burden. Burnout, sooner or later, leads to depression, which leads to cognitive decline, resulting in errors in clinical and administrative documentation, which are so damn expensive both for provider and patients we don’t know how it’s not addressed widely yet. (Well, we do know. That’s the above-mentioned hesitancy.)

So, doctors spend most of their patients time dealing with EHRs. It’s like tedious, boring, but very important work within another work — which is providing care. Obviously, nor them, neither patients are happy with the situation.

Wonderful things about AI is that it can beat humans in chess, but it can’t invent chess, yeah? So, while Suki.ai — it’s a digital voice assistant for physicians — listens to exam room conversation and waits for a command to create a clinical note, doctors get to empathize with patients, communicate more efficiently, and be humans: inventive, clever, and understanding.

Physicians themselves believe that voice transcription tools with high levels of recognition and good NLP behind are the technology that is able to reduce the burden — and it kind of does. Suki’s website has lots of success stories reporting reduced time dedicated to making notes in the exam room by 70-80% and improved quality of physicians’ life. Suki can be integrated with hospitals’ existing EMR.

EHRs companies can also be proactive in the matter of enhancing their software with robust voice-enabled assistance - Epic, for instance, partnered with Nuance — one of the most popular speech-recognition AI-driven technologies on the market — to do so.

Another company is Dragon Ambient eXperience (DAX) — technology that works by the same scenario: listens to conversations in the exam room, contextualizing it, and creating documentation from these data. Surely, the invisible scribe who makes it possible for doctors to focus on their relationship with patients boost both their and doctor satisfaction. Another company, Notable, offers clinicians to use voice recognition technology and attentive AI listeners using their smartwatches. Data gets right into EHRs, — and patients can get access to their info, related to the appointment. Notable’s app can even recommend, per request, fitting billing codes for every case.

Scheduling and routing can be easily solved by giving patients voice-enabled devices that connect them to doctors and nurses, as Orbita did. In such a way, patients can address their concern right when they felt the need to, without waiting, and nurses get to prioritize instead of going through each patient in their care and seeing everything is pretty fine.

Same listening-recording technology will be probably available for the surgeries in the nearest future: surgeons will voice about what they’re doing and won’t have to decipher notes afterwards. Moreover, they will be able to use the concluding notes as a tool to analyse their cooperation with assistance, performance, and even level of stress. For instance, Kevin Seals, technologist and doctor, develops so-called surgical concierge, that helps surgeons get needed information via voice commands, hands-free — a useful device for a sterile environment.

Voice-enabled decision support systems will be very helpful in the future — right now, they’re quite rare. First of all, due to security reasons. Second of all, doctors and engineers have yet to figure out the right balance between “helpful advice I’ve asked for/I didn’t notice” and “annoying tips that cause migraines” in tech that is offered to hospitals.

Personally, we believe that the solution lies in relentless collaboration with healthcare professionals.

Last year Orbita’s report found out that, while voice assistants adoption in the industry is really slow, more than half of respondents from healthcare organizations want to employ such a use case. All generations — from the consumers’ side — are more or less equally interested in the voice-assistant healthcare tech. So we’d likely to see more of these in the future.

If you want to hear more from tech in healthcare from us, please, subscribe to our newsletter.

Tell us about your project

Fill out the form or contact us

Tell us about your project

Thank you

Your submission is received and we will contact you soon

Follow us