Building apps for chronic pain management

This is an article about apps and desktop solutions that help people deal with chronic pain. Earlier, we wrote an installment on how to build CBT-based apps for those who live with mental health disorders, and you can read it here.

Before we start talking about different features you might want to include in your app, if you decided to help people deal with chronic or acute pain, it seems like a good idea to cover a bit of a science of pain and an efficiency of managing it through digital tools.

Science behind chronic pain and digital pain management

Pain becomes “chronic” when it lasts more than three months or 12 weeks, and about 30-50% of the worldwide population suffers from it. Most common chronic pains are back pains, headaches of different caliber, migraine included, and joint and nerve pains, but this list doesn’t even begin to cover all the variety of pain-related conditions. The causes of chronic pain also vary: it can appear after physical or psychological trauma; after surgeries; it can occur due to stress or different diseases; it can come with an age.

Now, the most efficient pain assessment framework is biopsychosocial. It explains pain, not as a reaction to injury which appears in equivalent to the intensity of the damage, as people believed the pain was before. The biopsychosocial model rather addresses pain as a complex “pain system” that gets activated not only by illness or physical trauma but also by environmental, sensory, cognitive, behavioral, cultural (!) and other factors.

Psychological and neurological consequences of dealing with chronic pain are immense. There is, for instance, a phenomenon called central sensitization — when the central neural system gets so sensitive that it interprets the tiniest, not damaging stimulus as painful. Chronic pain’s “besties” are depression and anxiety — the longer people experience chronic pain, the more vulnerable they become before these two. Chronic pain affects emotions, mood, sleep, memory, focus. It changes how people work, socialize, perceive themselves — and, contrary to popular belief, pain doesn’t bring strength.

For some conditions that are accompanied by chronic pain, there are treatments; for others, there are only medications that help to alleviate symptoms (painkillers, sometimes antidepressants); and, surely, there’s therapy, physical exercises, meditation, and fundamental lifestyle changes.

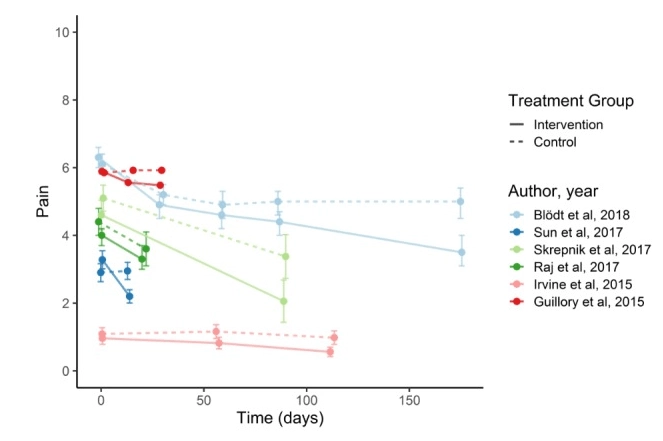

To provide, among other things, the latter, digital solutions come. They don’t help everyone, their clinical effect sometimes is not grandiose, and there is certainly not enough long-term studies to assess their general efficiency — but people who used apps for pain management became less anxious, had more resources to cope with pain and reported that their awareness, knowledge, and quality of life improved.

So: it’s worth it. The primary, “low-level” goal of pain management apps is not to eliminate pain, but to help users learn more about its nature and to understand what affects it, — cope with it, in general. Pain reduction is often a consequence of learning and therapy. Such solutions are very important for out-of-hospital treatment and self-management: they drive patient empowerment and independence.

What patients want from pain management apps?

“The daily life from before is not yours anymore. You need to find a new normal. And in that process, it’s important to have a tool…”

That quote from above is from a patient who participated in the April’s qualitative study on what patients want and expect from eHealth pain management solutions — the whole concept of the main mission of such apps in three sentences. Everyone except one respondent of the study could imagine where these apps may be of use in their daily life.

The study splits what patients want from digital technology into three categories:

- They want to get knowledge and information about their condition;

- They want tools, recommendations, features that help them find balance;

- They want tools and exercises to improve communication and their social lives.

The list can become a starting point for any chronic pain self-management software.

(!) Obviously, if there are tissue injuries, such app can’t be used as the main healthcare tool (just saying.)

1. Features to provide information about pain management

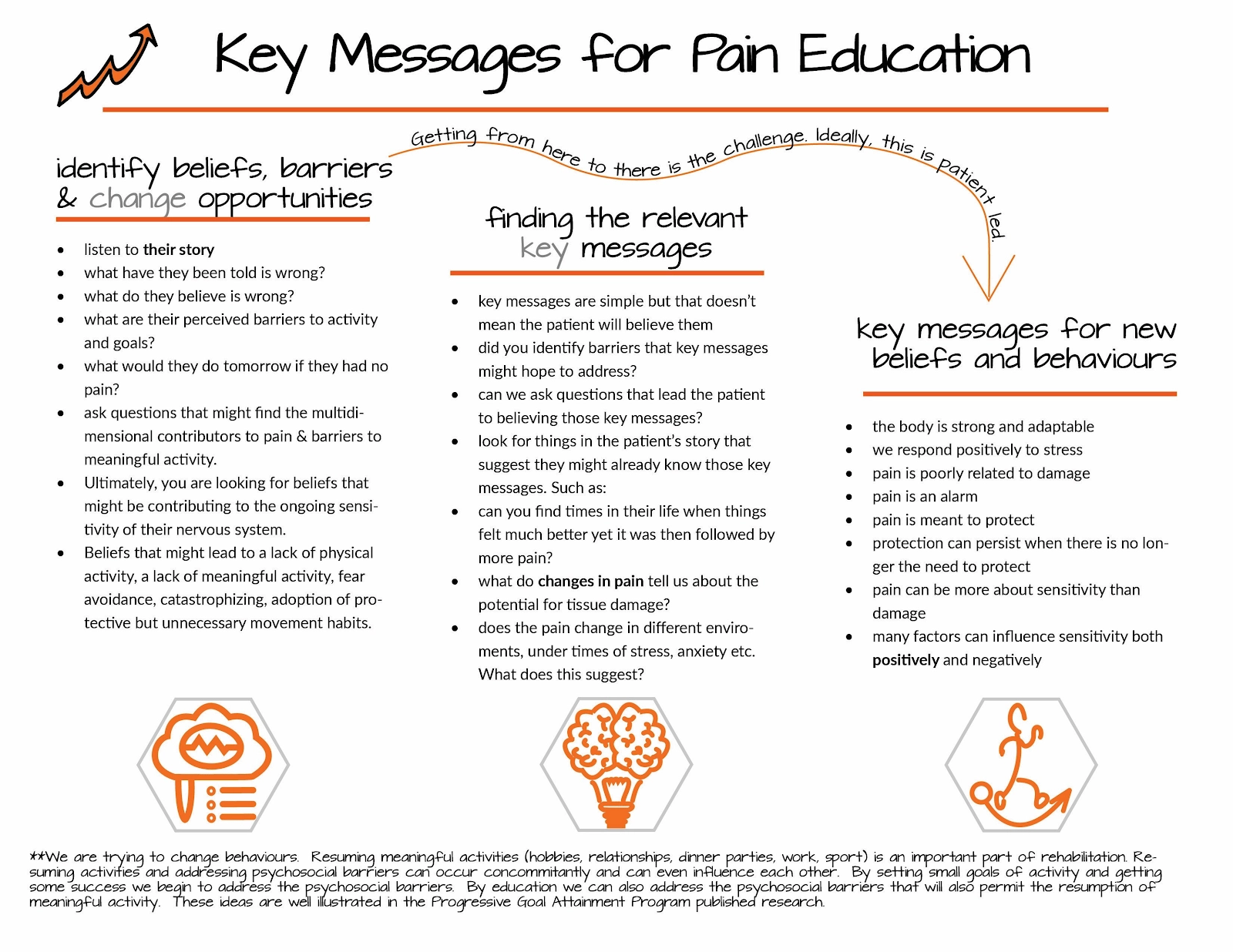

One of the main messages which can start your “deconstructing conjecture” learning program in the app is that pain is more about sensitivity than injury (that’s Greg Lehman) and that the main objective isn’t to fix something that’s wrong but to help users start to experience good things again. There are also some pain science messages you can choose to focus on.

Blocks that drive education and awareness about how to deal with chronic pain and its physiological and psychological consequences. As we’ve already mentioned, there is a number of unpleasant and challenging changes patients with chronic pain experience. Often, they don’t know how to deal with it — and if they should deal with it at all (fear-avoidance attitude is well-known here).

Yet, those who start gaining more knowledge about what to expect from their condition and from themselves while dealing with chronic pain, feel less uncertainty and frustration about it. Information is power, partially because when we understand something, we feel we can control it. So learning blocks about the nature of chronic pain will empower your users, make them feel independent and safe, reassured, smart. Which is vital for one’s self-image —and for pain management.

Don’t forget about making all complex scientific material understandable for your patients.

As an example, Pathways begins its pain relief program with education: how pain works, what makes the pain system overactive and oversensitive, and why it often “malfunctions.”

The app combines cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and biopsychosocial pain assessment and management. Users explore pain as a system, influenced by different factors, and learn to recognize their impact on their behavior, mind, emotions, and physical state.

Contact with physicians. Make sure your app connects users to customer support (or patient support? We should employ that term), the in-house medical team, or their physicians. Through chats, users will ask quick, itching questions about their state, share their therapy progress, etc. Talking to people who recognize users’ struggle and effort; have education and authority to alleviate users anxiety and doubts and reassure them; saw a lot of patients with similar conditions who made it through — make users feel safe, motivated, and recognized.

2. Features to help people with chronic pain establish balance

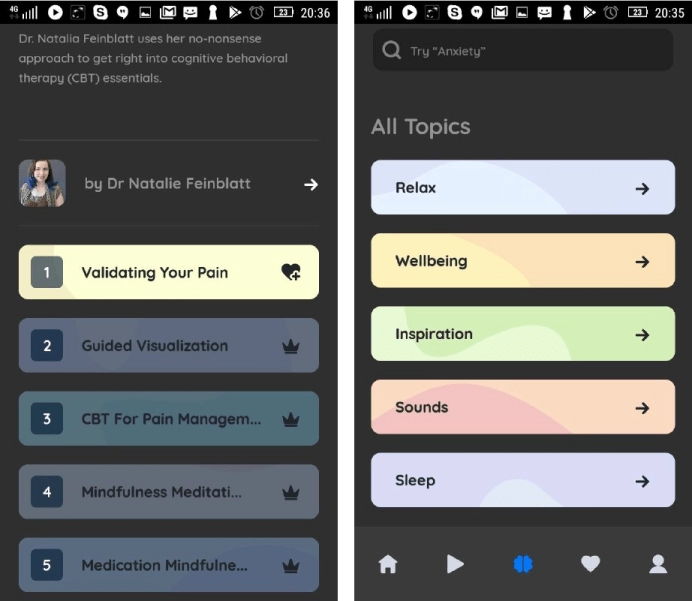

Providing information about what’s going on with people with chronic pain is just half of the deal. The other half — is to create tools and exercises that’ll help them unleash the power of CBT, mindfulness, and other techniques and help them to reinforce the learning. (In this article we talk about employing the CBT in the apps’ UX in more details.)

Data tracking and visualizing features for sleep, mood swings, the severity of pain and other variables. The general idea is if something can be put in numbers, put it in numbers, and, then, visualize it. That will break the complexity of pain at visible small parts. Users will understand that they don’t feel it, perhaps, all the time, that it shifts over their body as they move through days, that they are able to forget about it.

Besides, the biopsychosocial framework is sometimes hard to grasp and easy to turn into negative thinking (“ah, all of it is in my head, then. Very helpful.”). Data visualization features in pain management app will show users how the severity and frequency of their pain correlate with their stress, anxiety, irritation, and productivity; with their environment; with social situations they face.

Migraine Buddy, for instance, automatically tracks weather pressure and user sleep cycles, asks users to describe their attacks, then analyses input, and presents it as a report. Reports help users identify potential triggers and adjust accordingly.

A place for notes or diary. Notes is another tool for self-management, more explicit, personal, and explanatory than numbers. Armored with a CBT framework, users will recognize destructive patterns in their thinking, reflect on how pain, in different cases, affects them, and learn to work — on their “mistakes” with their perception.

Info on different journaling techniques — different approaches on what to write and how to write, like freehand — help people with chronic pain to control their focus better and, well, “be in the moment.” (That only sounds bad.) Being focused and aware of surroundings is important because it shifts their attention away from reliving the pain over and over.

Calendar and medication history. An in-app calendar, integrated with meds tracker, that doesn’t connect to other calendar services is a good idea for an app too. In such a way, pain-related things like medication plans, refill schedule, or appointments stuff don’t end up in people’s personal or work schedules. Optional push-notifications are enough for connection. Some apps, like My Pain Diary, allow users to save their health, medication and other personal data and convert them to PDFs users send to their doctors.

3. Features for socialization and communication in pain management app

Chats. As we’ve said, people with chronic pain often have trouble socializing — but feeling less lonely restores. So chats, where users bond over a shared experience, publishing platforms where they share their stories and receive feedback, support, and tips, and read other people’s stories are a must.

It’s a nice idea to provide an app with a feature of sharing their data with a community — give users an opportunity to see the progress of others and get motivation, inspiration, and strengths.

Communication recommendations. With pain comes the inability to put into to words and connect with loved ones. When you don’t know if you’re going to make it through a migraine attack, or a constant ache in the lower back is making you feel tired, constantly, it seems that there’s no opportunity to socialize. Due to that, people with chronic pain often feel isolated, abandoned, and guilty for the inability to fulfill their “social duties.” Along with chats and communities, we (and scientists) recommend including knowledge base and exercises on communication with friends, family, colleagues.

Personalize what you can

Sometimes people would feel down by charts that don’t change because they’re constantly in pain. A lot of apps also offer “words of wisdom” — motivational quotes about overcoming the struggle. It works for some people while it irritates others. It’s better to provide the “off” button for these features (actually, for as many features as possible.) Personalization is a way to win users’ appeal.

Pain crisis as the other side of opioid crisis coin

America is dealing with what seems like a peak of the opioid addiction crisis, and people with chronic pain are made to face its backlash. The prescription of opioid medications that are necessary for people with acute traumatic pain, people with complex regional pain syndrome, and people who are terminally ill, was limited after voluntary CDC Guidlines were released in the 2016 year.

Media started speaking about people who get prescribed with painkillers as of ones misusing drugs, — and a lot of doctors, by whatever reason, stopped prescribing them altogether. Public perception of opioid painkillers shifted: they essentially stopped being painkillers, and became “the first step to addiction.”

It seems logical. When there are many people suffering from chronic pain and taking painkillers for relief in the country, and there are many people dying from overdoses in the same country, it’s very tempting to make assumptions about the connection between the two.

But science has to have a say in it.

First of all, there is almost no correlation between prescribing painkillers and opioid-related death in the CDC’s reports; no trends between opioid overdoses and daily doses; no connection between people who get prescribed opioids and the frequency of their ER admissions (which is a popular speculation about this matter).

Without correlation, there can’t be causation. (Over)prescribing ≠ opioid crisis.

Second, despite the fact that regulations are all hell-bent on prescribing opioids for the third year in a row, there’s no decrease in overdose deaths number. Limiting meds for patients with chronic pains does not seem to be working against the opioid crisis, but it does, HHS thinks, drive some patients to get painkillers elsewhere or to commit suicide. Which is the opposite of healthcare’s main objective, and physicians do agree with us.

We want to recommend everyone interested in building or promoting their pain management solution not to market it as a “replacement” of opioid medications and not to use “fighting opioid crisis” label as something your solution can help with. Unless this is an app designed for people who want to beat addiction or you want to employ a feature of similar nature. People who want an app to manage their pain want to manage their pain, cope with it better, and reduce it.

Exploiting the opioid crisis discourse in there will unlikely add any value to their, already overwhelmed, well-being.

Get clinical expertise and involve patients in your app development

If you decided to build (or have already built) a pain management app, make sure to invite pain specialists and patients to test it. In long-term.

If you were asked by healthcare organization to build such an app — no difference, you still need to get an outside opinion.

People with chronic conditions say that, sometimes, their care providers have no idea how to handle the fact nothing is helping their patients. And how to deliver that fact in the empathetic form. (Physicians are not to blame, though, they do have a lot on their plate.)

Plus, sometimes pain management approaches are biased (so much for “bad posture”) or out of common sense (so much for “neurotoxins”). In other words, everybody makes mistakes. (Us too. If you notice them, send us a note!)

In order to get a comprehensive picture of information architecture you’ll use as a foundation for your app, you need to include patients and pain specialists in the development. Design interface and interactions in the app around techniques that really work. Make it accessible.

Apps for pain management are often built by pain scientists or people who suffer from chronic pain. They know all the nuances and bottlenecks, they know what to use to get better, they know things. Don’t miss the opportunity to create an effective healthcare solution from the start — invite them to participate.

Tell us about your project

Fill out the form or contact us

Tell us about your project

Thank you

Your submission is received and we will contact you soon

Follow us