Most common cyberattacks in healthcare and how to fight them

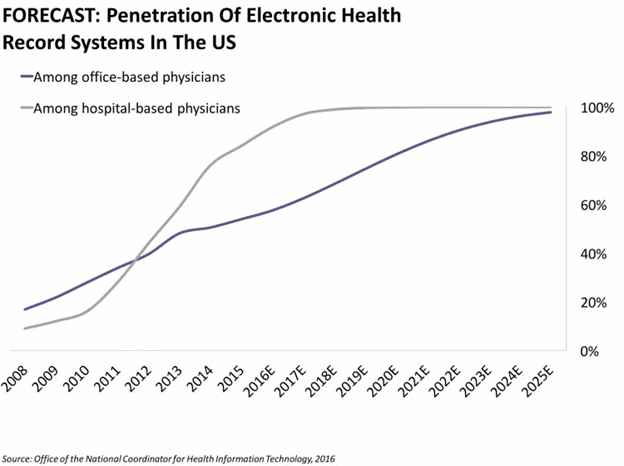

On January, 14, Microsoft celebrated Windows 7 end-of-life. According to the latest available statistics provided by Duo Security last June, nearly 56% of the healthcare sector used Windows 7.

We ran a survey to find out the current situation in the industry (by the way, if you work in the medical organization, please, participate here), but, according to current preliminary findings, the situation hasn’t exactly shifted.

The end of life for operating systems means no more mending fresh security gaps with testing and upgrades. PCs and medical equipment that are running on Windows 7 will be vulnerable before cybercriminals so in case your organization hasn’t completed transition, advocate for the upgrade.

Hackers love healthcare exactly due to hesitation to adopt the most basic security practices.

They also love private health information. In the depths of the dark web, they receive $1 for debit card information and $10 — for Jane Doe’s medical images and personal info. You can’t impersonate Jane after you receive access to her immediately blocked bank account, but you can if you have her patient records.

On the wave of the recent Windows 7’s death and the industry’s tentativeness towards the upgrade, we want to talk about the most common methods hackers use to snatch data out of your system or encrypt them.

Stolen (or guessed) creds

The most popular passwords are still password, and 0-7 and 1-8 sequences. People use the same (simple) password on multiple accounts. WordPress — or any CMS’ — credentials for the business’ website are often admin and admin.

If something above is relatable to you, your password has been exposed for a long, long time ago. How long have you been using it?

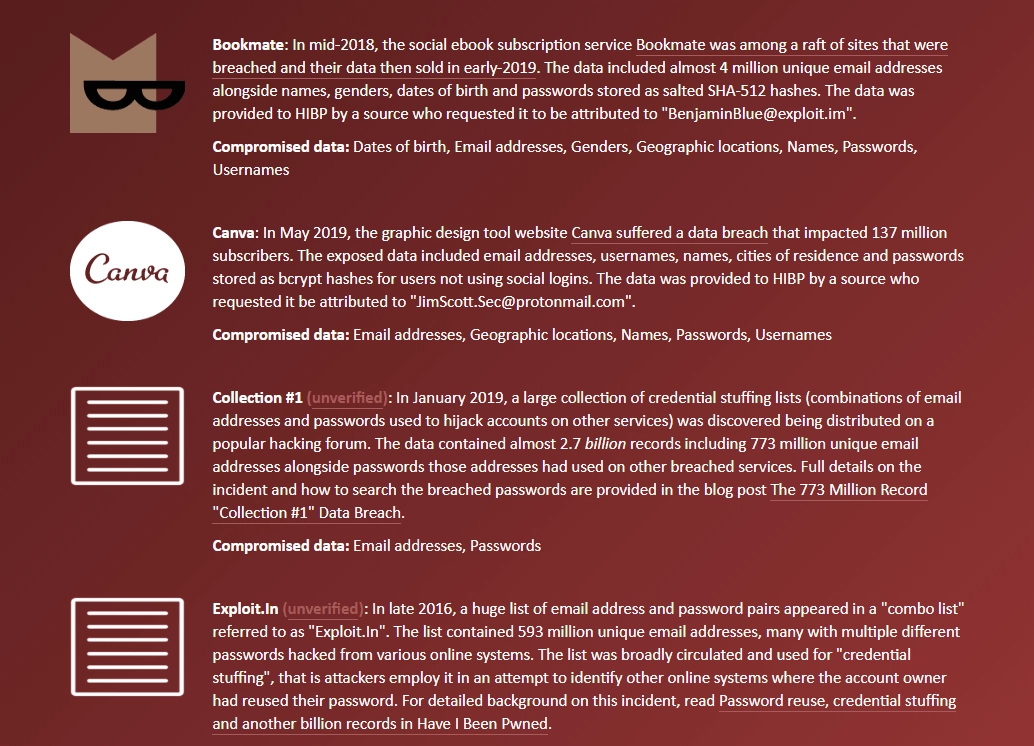

Last January, Troy Hunt discovered a large database dumped on MEGA cloud storage — about 773 million emails and 22 million passwords, compromised. To find out if your credentials are there, you can use Hunt’s resource have i been pwned? There are many dumps like this on the Internet. Not so large, perhaps, but still valuables and full of passwords, grabbed during attacks on the Adobe, Canva, tumblr and other websites.

How hackers apply databases with leaked credentials? They exploit your habit to use the same passwords everywhere and do what people call credential stuffing: a special algorithm tests every instance in that database against account hackers want to get access to. And, when they find matches, you’re pwned.

What you can do

Use complicated, unique passwords for every account in your possession. To be confident it’s complicated enough and someone hasn’t come up with the same idea, use Pwned Passwords to search for matches. To secure yourself more, set up two-factor authentication, so the system will send sign-in confirmation to your phone. Also, lock your phone.

What your security team can do

Ban attempts to log in to your server, site, or whatever after three tries.

What you shouldn’t do

Don’t write down your new complicated credentials and leave them in your cubicle/workplace. Please, don’t.

Phishing in the healthcare industry

New Year’s gift from Alexandria local hospital in Minnesota was a notification about a data breach of almost 50 thousand patients medical info: “employee’s account was accessed by an unauthorized third party.”

Another way for hackers to get into your account would be to send you an email with a link that will lead you to Gmail's “your session expired/confirm your credentials” page.

Except it won’t be Gmail’s page. It would be theirs, and they will see your complicated password.

That’s phishing: hackers use their knowledge of your email account interface and our coding skills to lay my hands on your letters. Despite the fact that healthcare is most prone to phishing industry, somehow organizations still refuse to conduct fishing tests and train their people not to get on the hook.

Such attacks also called man-in-the-middle (MITM) attacks, and they cost millions to the industry that could have spent this money on employee training.

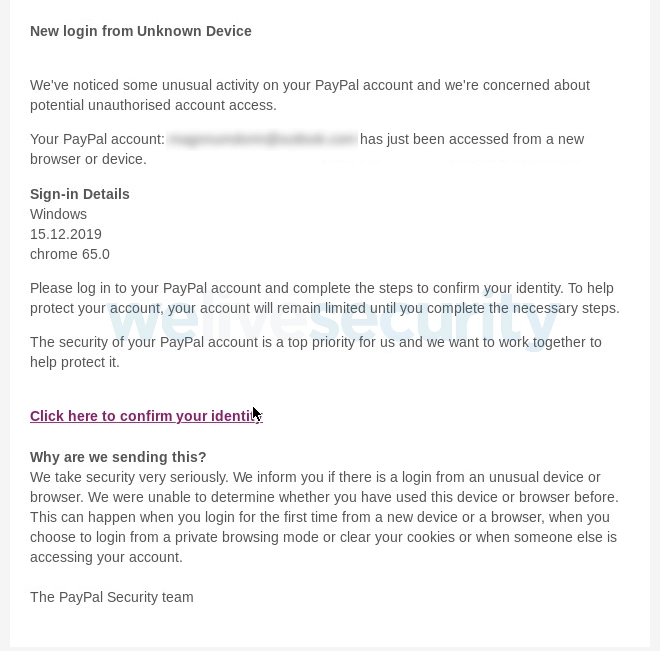

The example with Gmail is the simplest. Hackers could send you an email that will tell you that the security of your PayPal account has been compromised.

Then, they’ll ask you to write down your billing address and financial credentials, your answers on security questions, social security number; all the good stuff. Then, they’ll show you the page that writes about your newly “restored” access, but everything else will be stolen.

So, how you can protect yourself and your medical organization from being pwned via phishing?

What you can do: Protect your emails from phishing

Phishing is a social hacking technique, a combination of hacker’s knowledge about humans — about you — and their experience with technology.

Things to note, when opening a suspicious email from “familiar” sender (your bank, any other services you use, etc.)

- You aren’t addressed by your name, but you should have been. This is a case with emails from the bank or from any institution you’ve given your password details to. They will be addressing you by name.

- Letters with attachments. Although antiviruses rarely skip such an obvious hint on something malicious, there is still a chance they would.

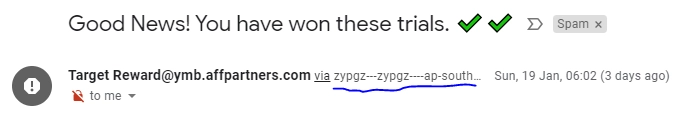

- Sense of urgency. When people are scared that something might happen, they tend to rush things. Banks would never want you to get a stroke after reading their emails (same as iTunes, Amazon, Facebook and basically any other brand that cares). That’s why when you’re logging in from an unknown device, you’re receiving a calm message “Your account was accessed,” not “URGENT!! Save your pictures with poorly drawn cats!” So, any sense of urgency in a title or body of the letter must spark a Doubt in the sender’s intentions. As well as exclamations. Same goes with messages about good news.

- CAPSLOCK. CAPSLOCK is a huge disrespect to a receiver, and no esteemed organization would use it. Even if they are legitimate, they have terrible customer service, so you’ll probably lose nothing by not opening an email. The same works for letters with large fonts.

- Letters on languages you don’t know. Treat that as a rule. If it’s an important purchase opportunity or a cold email, they should have done their research.

- etters from a brand without brand email. Pay attention if the email address is branded, especially if it’s a letter from a large brand.

- Letters without paragraphs & poor grammar. This is something a bit ambiguous, especially if your colleagues often write without paragraphs or if you correspond with foreign partners. Be vigilant.

- Carefully check the address bar of a link, it should be of the same domain the sender’s email is of, unless stated otherwise.

- If you see someone you’re familiar with asking you to rescue them, lend them money, follow some link to do something, don’t be shy to write an inquiry to confirm if that’s really them. Especially if you haven’t talked in a long time.

- “This message from a trusted sender” in the layout of the email or in any other field.

Scammers got everything right and you’re on the scam website. What you can do then?

Most people think the green padlock near the address bar of the website means safe, but it isn’t the case. Padlock represents presence/absence of SSL certificates (a tool that connects a website to a cryptographic key that maintains secure end-to-end communication and allows to transfer passwords and other sensitive information) and HTTPS (encryption type that also indicates the security of the page). But hackers often create malicious pages on sites where there are opportunities for third-party content, e.g. same WordPress or blog sites. Also, it’s easy to obtain HTTPs and SSL on resources like Let’s Encrypt.

In the past, our advice would be to look for Extended Validation (EV) SSL certificate, but right now it’s safe to assume that they are pretty much dead:

- there’s some confusion with green padlock UI over the different browsers, because it appears the absence of green padlock doesn’t convince people not to hand their credentials over — thus, it’s a lame alert indicator;

- green padlock sometimes appears not only for EV — thus, they can be easily acquired for fishing websites;

- sometimes, popular websites like Twitter or Facebook display owning EVs in one country, and not owning it in another (here’s wonderful Troy Hunt’s article about it.)

But. You’re on the site.

Here are some signs to look for (they may seem obvious, but there are a lot of people who are kind of forget about them because they were scared their accounts have been pwned, deactivated, etc.)

- Address line and the name of the site don’t match. It’s a landing page for Apple, but the address line leads elsewhere. Try googling what is written before .com/other domain and you’ll probably find some website that has no relationship to Apple whatsoever.

- Check address bar again. Here’s a nice example from a Wordfence

- Despite the fact that we've established that SSL certification indicators aren’t really reliable, you shouldn’t do anything on sites with a red indicator/or sign “Not secure”.

What your healthcare IT/security department can do?

- Web filters and blacklists are the first things that come to mind as well as restraining internet privileges, but these can slow people’s work down.

- Use the internal communication system (not Skype) for your institution. Actually, emails are not a perfect solution if you work in the medical organization and transfer PHI, because your end-to-end encryption, while present, is controlled by a third party. Messenger you’ve built for yourself — or with the help of a trusted vendor — is fully controlled by your specialists.

Malware in digital healthcare

Basically, malware is a software, but a bad one. Ransomware is a type of malware that encrypts all data on the victim’s computer and requires a payment/ransom to unencrypt the data. In healthcare, ransomware attacks are to be treated as breaches and reported according to HIPAA’s Breach Notification Rule, which is kind of explains (partially) why they are so visible in the industry.

How can you get ransomware? Well, phishing emails aren’t only used to get your credentials. They can plant malicious programs onto your computer, execute them, and — the rest is history; ransomware is very damaging for businesses. For instance, at the beginning of last year, Wood Ranch Medical, state California, suffered a ransomware attack and was forced to close the practice due to inability to recover data, encrypted by the attackers.

Malware can appear on your computer after clicking on the links, downloading files (love software from unofficial sources or randomly acquired WordPress plugins? yeah). They can plant it through access to your servers; through smartphone someone has used to connect to free WiFi. There are lots of ways. Harmful websites and emails are the most common.

What can you do to deal with ransomware in digital health:

- Don’t download files from unknown/suspicious sources;

- No software / anything that requires administrator’s privileges to install from unofficial sources;

- Don’t click on the links in phishing emails;

- Try to avoid connecting to free/public wifi from devices you bring to work;

What can your security/IT team do

- Antiviruses are not a remedy for all ills, but they’re still something. Utilize them.

- Encrypt hard drives and databases. This is a page from Security Rule recommendations, but seeing so many ransomware cases in healthcare, it’s hard not to repeat.

- Install access monitoring / incident reporting policies and solutions. You need to know about unauthorized/suspicious activity as soon as it occurs, so consider using incident reporting tools like OSSEC. All remote attempts to access should be logged.

- Scan for listeners in the network and shut them, if there’s any.

- Use/develop strong, secure software.

- Consider solutions that help to isolate browsing activities.

Another way malware can suddenly appear on your computer is through vulnerabilities inside the software you use. Which is why it’s essential to update all applications and platforms you use that interact with health information until the last version as soon as the opportunity occurs. Even FBI, alerting about ransomware attacks, urges people to do just that.

Cybersecurity is everyone’s business now, even if you can’t read a single line of code. Especially so.

Final words - cyberattacks in healthcare, how to fight

We spend a lot of time talking about cybersecurity in healthcare, but, while hackers are very fast and creative, the industry seems continuously surprised about the necessity to gain the same speed.

We often hear there are a lot of new tools hackers use to exploit people’s private information, but as you can see from this article, the most common way to grab patient data from healthcare is to write an email to an employee who didn’t get enough training.

Then, you appear in the system that isn’t secure enough because IT department doesn’t have enough money, and it’s done. In the first half of last year, an average of 37.2 breaches occurred each month. That almost a working week.

Let’s not be too easy.

Tell us about your project

Fill out the form or contact us

Tell us about your project

Thank you

Your submission is received and we will contact you soon

Follow us